Home > Archive > F.W. Kenny House > OWH article on the Keeley Institute

OWH article on the Keeley Institute

In The 1890’s, Alcoholics lined up for the Keeley Gold Cure

Sunday Omaha World-Herald Magazine March 25, 1990

By Yale Huffman (The author, is a Denver, Colo., attorney from Broken Bow. Neb.)

Clearing a century’s worth of debris out of the old Clifton Hotel in Blair, Neb., the Peter Sorensen family was restoring the place for operation as an apartment house Mrs. Sorensen riffled through a stack of yellowing papers dating from the 1890s. “Listen to this,” she called to her husband.

Sorensen paused to listen. Mrs. Sorensen read aloud:

“Absolutely reliable! There is neither doubt, experiment or uncertainty in this matter. We cure everybody who comes to us for treatment!

“If you desire to be rescued, saved, completely cured and restored, redeemed from the curse of drink, come to us and we will cure you!”

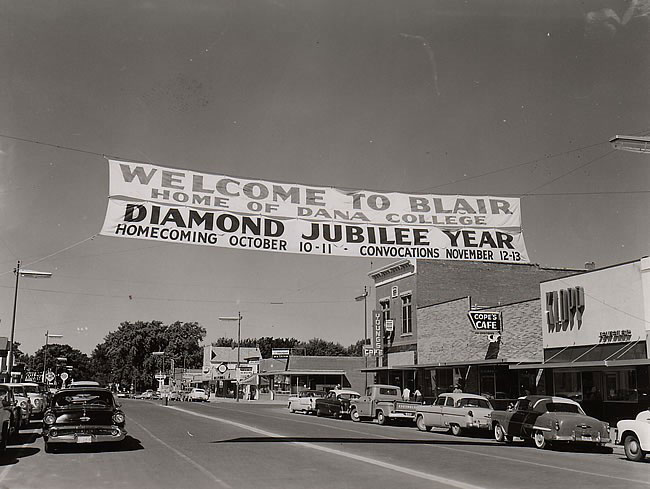

The Sorensens were discovering that they owned all that remained of the Keeley Institute, Blair’s main attraction 100 years ago. The place was built in 1891, sitting across Front Street from the depot. Alcoholics by the hundreds, finding the Nineties not so gay, found refuge here for the salvation promised by the Keeley Cure.

The Sorensens studied the pages of the advertisement and calculated the revenues. Rates were $25 a week, plus $5 for meals. Two people were assigned to each of the 25 rooms. Thus, 50 guests paying $30 a week produced $1,500 a week in revenue.

What was the attraction?

The gold cure. The answer was in the fragile papers.

“By the use of Double Chloride of Gold remedies discovered and perfected by Dr. Leslie E. Keeley, the liquor, opium, morphine and tobacco habits are completely and permanently cured … The remedies used by us mingle with and disinfect the blood, and totally destroy every vestige of the effects of dissipation, leaving the patient sound and healthy, giving a remarkable increase in nerve, power, vigor and strength.

“We give references of thousands who have been cured. Communications strictly confidential.”

Records at the Washington County Historical Association indicate men from across the country came to Blair for treatment.

“Some were benefited permanently,” said a May 1919 account in the Blair Tribune, “a few only temporarily, and others went right back to the arms of old King Alcohol as soon as they met him after being turned out as cured.”

Another story in the archives, “Lest We Forget – A History of Washington County,” by John A. Rhoades, went further:

“One of their rules in the cure was to allow the patients all they wanted to drink. Drunks could be found in the gutters and staggering down the streets at all times of day and night.”

Al Dunning of Omaha, a former owner of the hotel, remembers peeling some wallpaper off an old notice painted on a second-floor bathroom wall:

“Those Patients able to walk are requested to use the water closet on the first floor.”

Records at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., and the National Library of Medicine indicate the Blair facility was one of 118 gold cure franchises scattered throughout America and abroad at the height of the fad. Annual revenues passed $1.5 million.

Founder Leslie Enraught Keeley was an entrepreneur in the Horatio Alger tradition, with the flair of P.T. Barnum. Some said Keeley was born in Ireland; others said New York, in 1832.

Keeley wandered America as a youth, earned a medical degree from Rush Medical College in Chicago, and served briefly as an assistant surgeon in the Union Army during the closing weeks of the Civil War. In 1866 he was practicing medicine in the village of Dwight, III. Dr. Keeley delved into the writings of the ancient mystics. Later he would recall the experience.

“During my research into the leading authorities,” he wrote, “I met with a quotation from a work by Paracelsus, written at the close of the fifteenth century, in which it was claimed that Gold, the King of Metals, would be found in the coming ages a specific for diseases of the nervous system, like that of alcoholism.

“Following this little ray of light, which has threaded its way down through the centuries, I eagerly sought the sunlight of truth. My experiments were made in various salts of Gold used in medicine and, after countless efforts, the Double Chloride of Gold was discovered to be the remedy sought, and thus my remedy was brought into the world.”

Paracelsus did teach his Swiss students that “gold, the quintessence of the celestial fire, can remove the impurities of man and make him grow anew.” He prescribed that it be administered under certain conjunctions of the planets.

As recently as 1964 one pharmaceutical company was offering injections of gold sodium thiomalte for arthritis patients, but with the disclaimer that its “mode of action is unknown” and the warning that adverse toxic reactions “can be severe and even fatal.”

Neither Keeley nor the local pharmacist who helped him concoct the gold cure would disclose the formula. It was injected by hypodermic, requiring a physician qualified to wield the needle.

For guaranteed cures to take at home, twin bottles labeled “Keeley Treatment for Inebriety” were $9 a pair. The 20 percent alcohol content was declared on the label.

The rest of the formula remained a secret until critics and rivals published their analyses: water, glycerine, willow bark, ginger, hops, coca, aloes, atropine, pilocarpine, apomorphine and strychnia. The apomorphine and coca were included to make the patient feel good if the stiff dose of alcohol did not suffice.

A modem scholar offers his analysis of the gold cure. Professor H. Wayne Morgan in his book, “Drugs in America,” concludes that “whatever the precise nature of the compounds, they clearly relied on tranquilization and antagonism for effect. Some relaxed and stupefied the patient while others created a temporary distaste for alcohol … As for gold, its presence, if any, was hard to detect, and it had no therapeutic value, but had strong symbolic appeal.”

Morgan speculates that whatever gold may have originally been included was later discarded because of adverse side-effects. Dr. Jeffrey Walder, a clinical psychologist in Maryland, is more succinct. “There is no cure so preposterous that it won’t work for somebody.”

Dr. Keeley announced in 1893, “We will fill no further orders for home treatment for less than a full set of five bottles, that number having been found necessary for a complete cure. Price $22.50.”

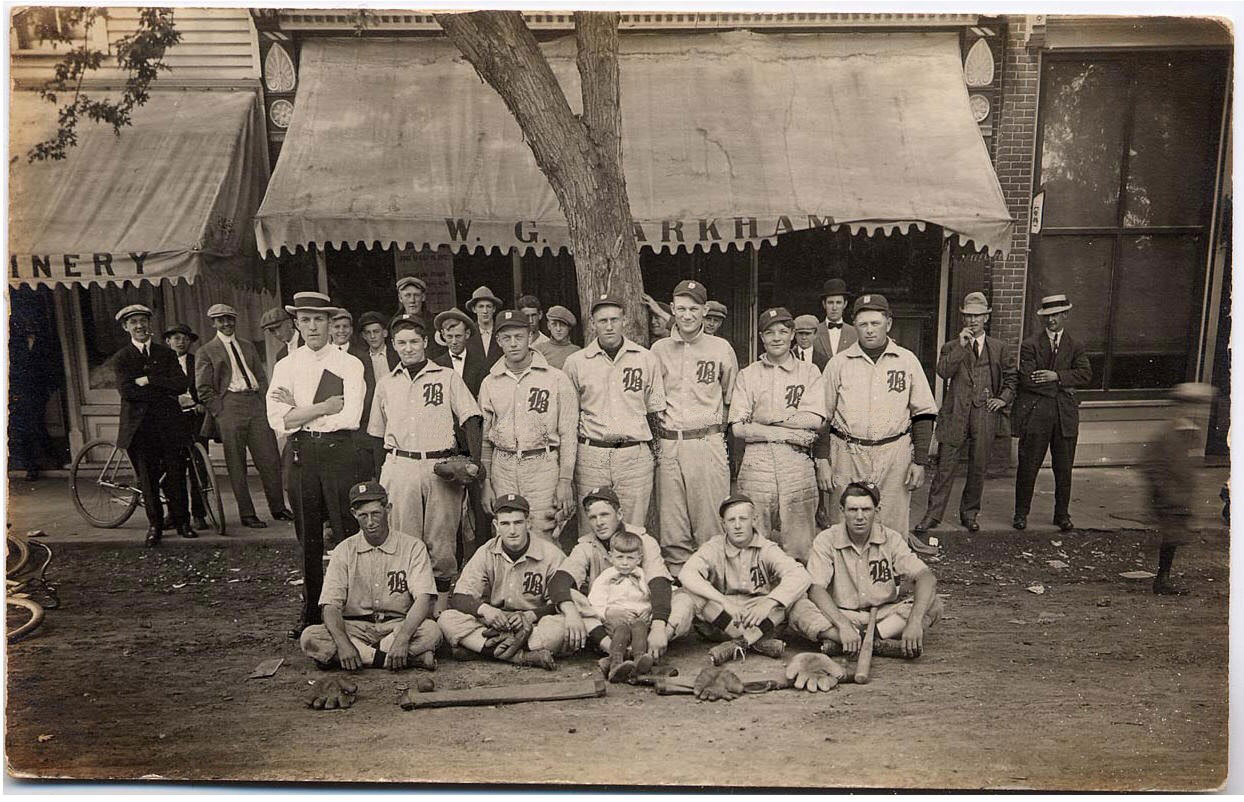

The hypodermic gold cure was administered to patients from jealously guarded supplies. Layers of red, white and blue liquid were visible in the ampules containing the mix, which came to be known as the barber pole. OUR TIMES DAILY the men lined up in shirt sleeves for the ceremony which they called “passing through the line.” Something in the mix left a faint yellow tinge at the puncture, as if to verify the gold content.

The few women who came to Keeley got their shots in the privacy of their rooms, segregated from the men’s quarters. Patients were allowed all the whiskey they wanted inside the institute, but anyone who drank outside was discharged, with no refund. The remedy included a substance to produce acute nausea when alcohol was ingested by the patient.

Rudy Fick, the 83-year-old retired sheriff of Washington County, recalls stories of violent reactions by patients in downtown Blair.

Another Nebraskan, reminiscing at last year’s AA Old Timers banquet in Omaha, recalled his own discharge from the Keeley Cure which was operating in Council Bluffs in the 1930s, Arriving home in O’Neill, he met up with an old drinking buddy.

“Never again!” he vowed. “Never a drink?” asked the friend. “Never the cure!” came the reply.

Keeley therapists regarded a “cure” as detoxification, withdrawal from alcohol and discharge. Many patients finished their month of treatment in a state of euphoria. Beyond the mood-enhancing drugs in their medicine they had been well-fed, exercised, bathed, massaged and emotionally nourished by constant encouragement from fellow alcoholics. Many went home in buoyant spirits, cured by Keeley standards.

Dr. Keeley declared that any relapses were due to the patients’ failures to follow directions.

“I cannot paralyze the arm that would raise the fatal glass to the lips,” he warned.

The Gay Nineties suffered an epidemic of alcoholism that swept across America and the Keeley Cure caught the wave on the rise.

Commencing with the first franchise in Des Moines in 1890, the gold cure was offered in 28 cities within a year. The franchises peaked at 118 in 1893. By the end of the century, Dr. Keeley claimed 400,000 cures, with a recovery rate of 95 percent.

The Midlands were fertile ground for Keeley. At one time in Nebraska there were gold cures in Lincoln, Omaha, O’Neill and Grand Island. The 1891 incorporators of the Blair franchise included Dr. B.F. Monroe to assure medical endorsement.

Dr. Keeley introduced the disease concept of alcoholism and won endorsements from the temperance societies. The Chicago Tribune checked out his claims and applauded the results. The Army assigned alcoholics to him for treatment. He spoke as an evangelist from pulpits throughout the land. The Minneapolis Tribune called him “the patron saint of drunkards.”

Contemporaries spoke of his personal magnetism but described him as “a born autocrat with a combative temper.”

It was during the brief years of ascendancy that Dr. Keeley was to enjoy his moment of triumph. Returning from a franchise mission to Europe he emerged from the depot in Dwight to discover his route home lined with employees, patients and alumni of the Keeley Cure.

Nine hundred men and women stood along, the curbs in silent tribute.

“My God!” exclaimed the doctor. “What a sight!”

A patient standing nearby responded, “As our earthly savior, it is your rightful due! ” By this time, many physicians couldn’t stand Dr. Keeley’s prosperity. Professional circles buzzed with protest. The flamboyant gold cure ads roused the Illinois State Board of Health in 1881, and Dr. Keeley’s medical license was revoked. Thereafter, he referred to his patients in Dwight as students.

Detractors in the medical societies of Boston, Chicago, Memphis and San Francisco went on record with criticism of Dr. Keeley’s methods and his secrecy about the formula. Unethical, said the critics. Dr. Keeley’s strenuous defense of his right to profit from his discovery, as any inventor might, did not soothe his medical peers.

“He dominated everybody and made them do as he wanted them to do,” recalled an early associate. “If they would not do it, he would make them do it or have nothing to do with them at all. That was Keeley’s character.”

The transcripts of medical society proceedings also quote defenders who argued that, after all, conventional medicine was doing nothing for alcoholics and Dr. Keeley did have some successes where others had failed.

Nevertheless, his estrangement from his medical colleagues widened as his business prospered.

Speedy growth carried risks. The rapid expansion of Keeley franchises brought problems. Not all investors were altruistic and the profit motive tended to dominate the treatment. Personnel problems multiplied within the institutes. The binges of former patients brought derision.

Legal problems arose in the mid-1890s. In Blair alone, the Keeley Institute was sued by four people within one seven-month period.

The Blair Pilot in 1899 reported that “a former patient was attempting to sue Manager Eller on charges that the Keeley method guaranteed cure for the liquor habit and he had not stayed cured.”

Patients around America were demanding refunds or filing claims for injurious side affects of the injections. The International Medical Magazine featured an article titled “Insanity Following the Keeley Treatment.”

Keeley alumni, disturbed by the failures within their ranks, came to realize that something more than detoxification was needed to stay sober. Recalling the communion formed when passing through the line,” some graduates formed a society to prolong the fellowship. They founded the Keeley League to refer new prospects to the various institutes and to welcome them home afterward. Alumni reunions at each facility attracted grateful alumni and their families. Wives formed a women’s auxiliary.

National conventions of the Keeley League drew thousands. Bands played the Keeley Grand March. The festivities ran like revival meetings, with Christian overtones. Prominent men gave personal testimony and gained fleeting celebrity as victors over Demon Rum.

At its height, the Keeley League claimed 370 chapters nationwide. “Group threrapy” was a term yet to be invented, but 30,000 members were practicing it in the 1990s. Their common talisman – the tin cup chained to the town pump in Dwight – was their symbol. Each wore a lapel pin fashioned of a capital K enclosed within a miniature golden horseshoe.

But for every sober graduate there were more conspicuous slippers. They were expelled from the fellowship and their notoriety disillusioned the public. The cure business fell off as the century moved toward its close and Dr. Keeley retired to a home he built in Los Angeles.

Dr. Keeley said he had left the field of medicine. “Without severing connection with the profession,” he wrote, “the tie in time fell to pieces.”

He died of heart failure in Los Angeles on Feb. 21, 1900, a millionaire. The Keeley League, bereft of its leader, did not survive him long. His widow endowed the Christian Scientists with much of the wealth mined by the gold cure. They left no children.

The various Keeley Institutes dropped into insolvency and dissolution in the years that followed. The Blair facility became the Clifton Hotel and the cure operation moved to Omaha. It was still advertising in The World-Herald in 1909, but soon faded away. The Grand Island franchise was the last Nebraska survivor, closing its doors in 1918.

Prohibition arrived, but some patients were still referred to the Keeley Institute by the Veterans Administration. The home office in Dwight persevered, striving for survival with treatments for cocaine, morphine, opium, heroin, tobacco and nervous disorders.

By the time liquor was legal again in 1933, Alcoholics Anonymous was just around the corner, offering recovery with no dues or fees.

By 1950, the Keeley patient load had dwindled to 511. The management in Dwight offered its rooms for AA meetings and the Keeley Cure was abandoned altogether in 1966.

Morgan, in an epilogue to the Keeley saga in “Drugs in America,” wrote: “Had not Keeley begun with the gold nostrum, and later been committed to the defense of his formula and his own ego, he might truly have become an acknowledged prophet. His method merged self-help and group therapy, which were the real basis for his frequent successes, and precursors of the AA program which was to emerge later.”

Today in Blair, the Keeley Institute, restored and rechristened the Landmark Inn, offers living quarters to new generations.

Adjust the text size

Featured Pictures

Archive Links

BHPA Links

Blair Historic Preservation Alliance | P.O. Box 94 | Blair, Nebraska 68008 | contact@blairhistory.com